Liturgical Fragments at the Library of the University of Southern Denmark

Research Assistant Steffen Hope tells us about his work with the SDU library on identifying medieval manuscript fragments in the library's early modern books.

The collection and the project

In the past few months, the Centre for Medieval Literature and the University Library of the University of Southern Denmark have been collaborating on a mini-project concerning medieval fragments found in a collection of old books in the university library’s possession. This book collection once belonged to Herlufsholm School in Næstved on Sjælland, and in the 1960s the collection was purchased by the university library of what was then Odense University, which is now part of the University of Southern Denmark. Herlufsholm School was founded in 1565 by Herluf Trolle and Birgitte Gøye, husband and wife, and from the sixteenth century onwards Herlufsholm accrued a significant number of books, some of which were produced in Denmark and some of which were purchased in other parts of Europe. Several of these books were donated to Herlufsholm by book collectors who had spent considerable time and money buying beautiful books from various parts of Europe. As a consequence, the Herlufsholm book collection contains several books from England, Germany and Switzerland. All of these countries, along with Denmark-Norway and Sweden, took part in the Protestant Reformation, which meant that as monasteries were dissolved and religious life brought into a Protestant framework, large number of books were confiscated, cut up, and then recycled as material for book-binding at printing presses. In the course of the Reformation, then, a large number of books were destroyed, and only survive in fragments large or small, scattered among books from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Some of these fragments have been the focal point of the mini-project at the University Library of Southern Denmark.

The main purpose of the project has been to identify and catalogue the fragments that can be found in the book collection. Only an estimated fraction of these fragments are known to us at this point, because the collection itself contains a vast number of books that will require years of concerted research. In the project, therefore, only a small number of books and their fragments have been subject to closer scrutiny. The project has been carried out by two researchers: first and foremost Jakob Povl Holck, research librarian, who has already worked on some of these fragments for three-four years, and then myself, whose main task has been to identify the liturgical fragments and uncover as many details about them as possible.

A large number of medieval fragments in early modern books originate from liturgical manuscripts. As the Reformation supplanted Catholicism with Protestantism, the books for the Catholic liturgy were considered outdated and useless and were discarded and recycled in high numbers. Furthermore, as any given Catholic institution – a monastery, a cathedral or a church – needed several books for the performance of liturgical ritual throughout the year, one single institution contained plenty of material for recycling. This dual factor – the number of institutions and the number of liturgical books per institution – explains why so many of the surviving fragments come from these books used in the mass and in the office cycle.

The main purpose of the project has been to identify and catalogue the fragments that can be found in the book collection. Only an estimated fraction of these fragments are known to us at this point, because the collection itself contains a vast number of books that will require years of concerted research. In the project, therefore, only a small number of books and their fragments have been subject to closer scrutiny. The project has been carried out by two researchers: first and foremost Jakob Povl Holck, research librarian, who has already worked on some of these fragments for three-four years, and then myself, whose main task has been to identify the liturgical fragments and uncover as many details about them as possible.

A large number of medieval fragments in early modern books originate from liturgical manuscripts. As the Reformation supplanted Catholicism with Protestantism, the books for the Catholic liturgy were considered outdated and useless and were discarded and recycled in high numbers. Furthermore, as any given Catholic institution – a monastery, a cathedral or a church – needed several books for the performance of liturgical ritual throughout the year, one single institution contained plenty of material for recycling. This dual factor – the number of institutions and the number of liturgical books per institution – explains why so many of the surviving fragments come from these books used in the mass and in the office cycle.

Liturgical fragments and their challenges, part 1 – all shapes and sizes

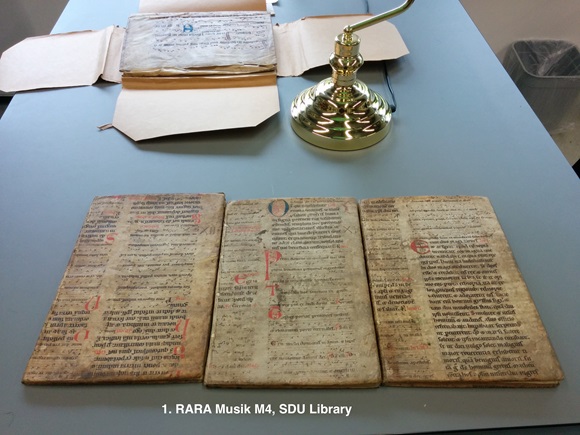

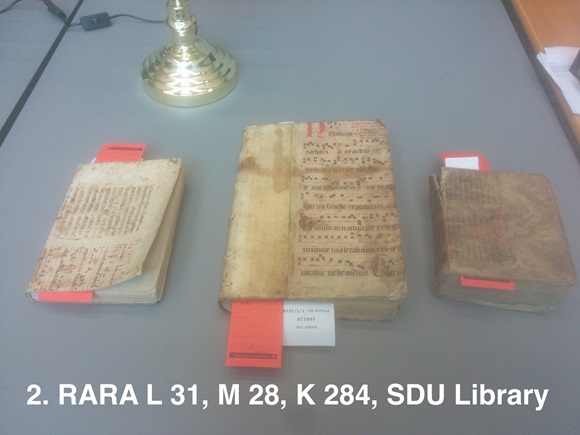

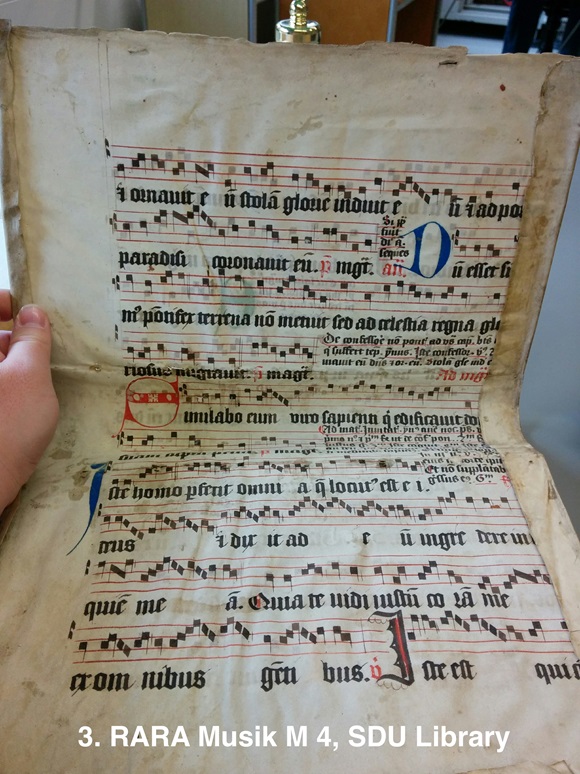

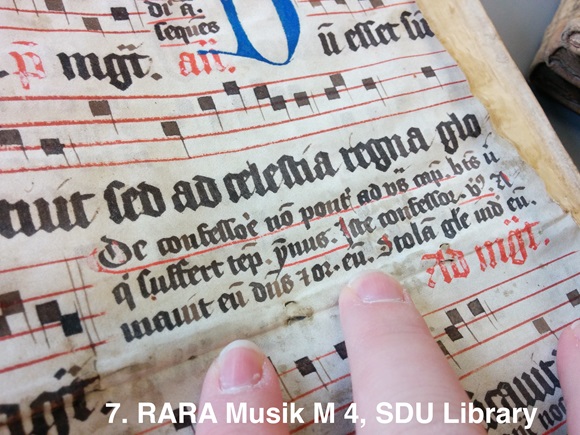

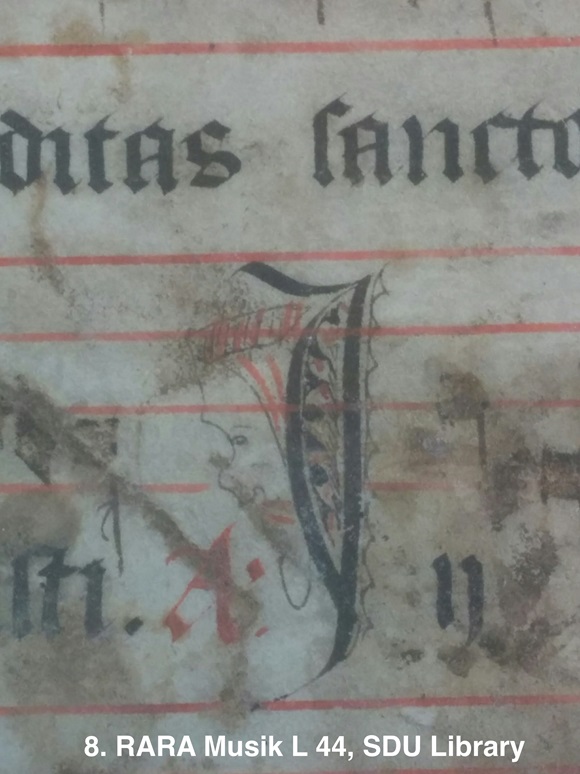

Manuscripts fragments are like miracles, in that they come in all shapes and sizes . In some cases we have a complete page where both the recto and the verso sides have legible text. In other cases we have one complete recto and one complete verso but from different pages. There are also variations of these where the text is more or less legible, or where the pages are more or less complete, but where it is nonetheless relatively easy to access the content. Then there are those minute fragments that have been cut into such small pieces that there is hardly a single word from which it is possible to identify what the original text has been. The fragments in the Herulfsholm collection provide a very wide variety of such cases. Among the fragments that have been easier to deal with is one from RARA Musik M 4. This fragment is a complete surviving page where the text is legible and written with big letters and space between the lines. The only challenge here has been to untangle the condensed information found in the liturgical commemorations, which are short mini-services performed within the main service of a feast-day, and where the information about the chants to be used is heavily abbreviated. I will address the complexity of these commemorations in more detail in the next section. For now, suffice it to say that despite the condensed information, the size and the state of the fragment has made it easy to identify the texts.

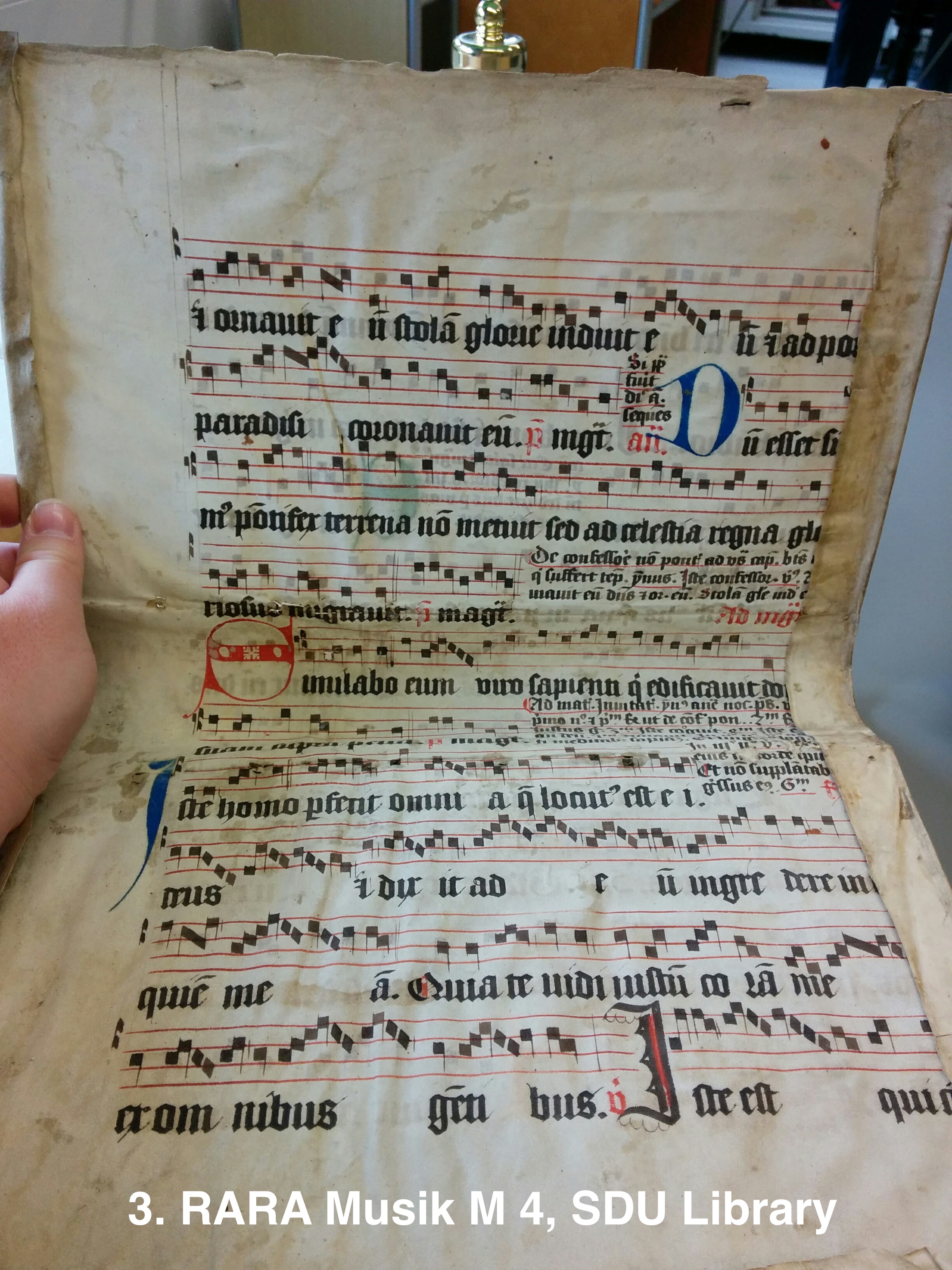

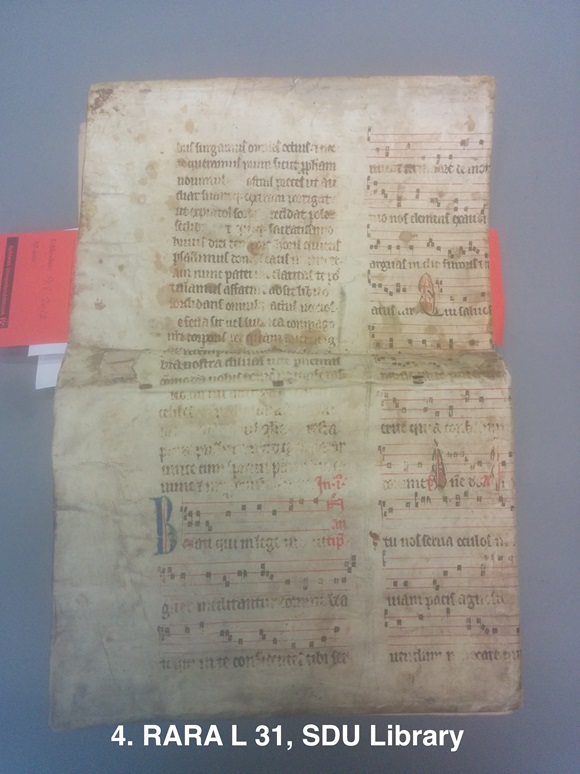

Similarly, fragments such as RARA L 31 also provide a much easier case for identification, since here the manuscript has been cut vertically, so that almost the entire page has survived.

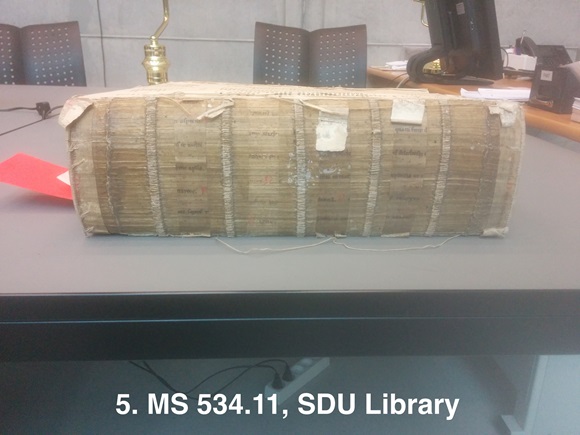

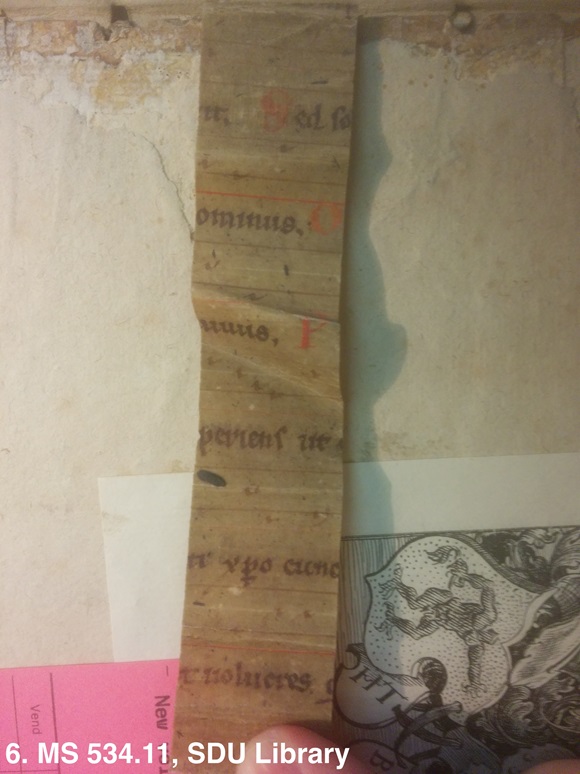

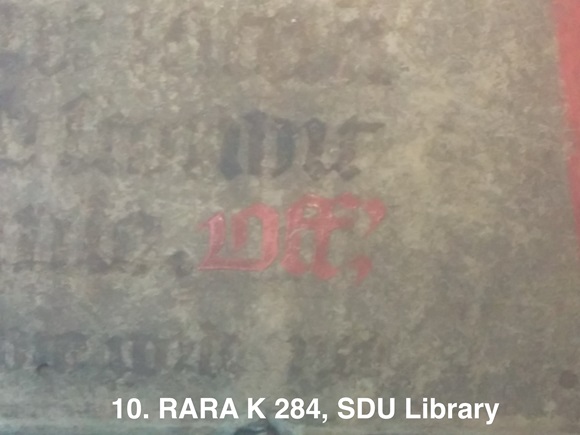

On the opposite side of the spectrum, however, we find the case of MS 534.11, where the surviving fragments are seven narrow strips cut out of a manuscript. Six of these are used to strengthen the spine of the book, and of these six only two are cut in such a way that they contain coherent strings of words. The remaining four, however, as well as a seventh standalone fragment, are cut vertically, so that the text contained in each fragment is comprised of excerpts from six-seven lines. For each of these lines there might be one complete word, or there might be the ending of one word and the initial of another. Fortunately, there are databases of liturgical chant that make it possible to identify a chant even though there is very little information to go on. But sometimes there just isn’t enough for identification to be made, and we are then left wondering what chant it belongs to, what part of the feast-day it belongs to, and even what book it belongs to. In the case of MS 534.11, there have been enough material to allow for the identification of five of the seven fragments have been identified as belonging to a missal, but for the remaining two the identification still remains a mystery.

Liturgical fragments and their challenges, part 2 – decoding liturgy

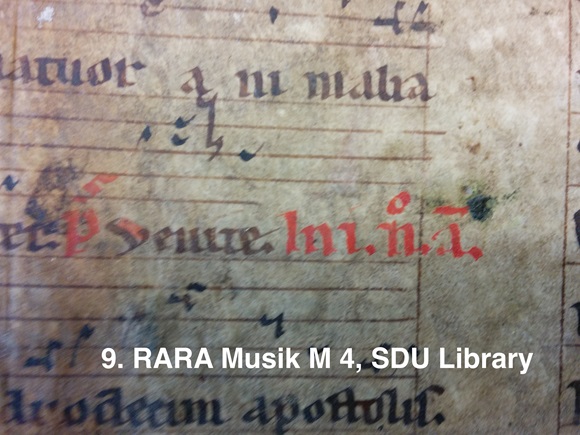

For any religious institution of medieval Christendom, the most important part of the daily round was the performance of liturgical chants and readings. There are two main forms of liturgical celebration. One form is the mass, which is a single service centred on the Eucharist. This celebration is comprised of many types of chants that are specific to the parts of the mass. For instance, there is the offertorium, which is a chant performed as a part of the Eucharist and only then. There is also the sequence which consists of non-scriptural verse material sung at a specific place in the mass. The other form of liturgical celebration is the office, which consists of eight services spread out through the day, with the most important service being that of Matins, celebrated roughly three hours after sundown, and the second most important being Vesper, celebrated around six hours before Matins. Since these are the longest services, the liturgical books for the office most often contain the chants and readings for Vesper and Matins, and sometimes also Laudes (performed three hours after Matins).Due to the complexity of liturgical celebrations, the books containing the material for these services need to record a lot of details. In order to save space, the information within a liturgical book can often be very condensed, leading to abbreviations, shorthands, and the reference to chants by their first words only, i.e. their incipits. This condensation of information is the other big challenge when working with liturgical fragments and trying to assess what type of celebration is being referred to in the fragment. Fortunately, this condensation of information is bound by rules that are common to all of Latin Christendom, which means that in order to decode a page of liturgical information you only need to be familiar with the abbreviations and the short-hands used to indicate what type of text we are dealing with, and where in the service the text belongs. This leads us back to the commemorations from RARA Musik M 4, where the information is even more condensed, as can be seen below. The condensation of material is in and of itself not a major obstacle, exactly because there is an established custom for how the information is condensed. The challenge really lies in those cases where the state of the fragment, or the state of the text, makes that information less legible, and where we have to spend a lot of time building up the context around the condensed information in order to draw some form of conclusion.

The text of the commemoration indicates that it is for a confessor who is not a pope, and the commemoration is to be celebrated at Vesper. The texts to be performed are one capitulum with the text “Blessed is the man who suffers temptation” (from James 1:12), a hymn with the incipit “This confessor”, a versicle that reads “God loved him and adorned him and clothed him in glory”.

In addition to these commemorations, there were also several elements of the services that were indicated with heavily abbreviated pointers, usually in red letters. For instance, psalms are indicated by “ps”, antiphons with a simple “a”, and then there is the heavily contracted note that points to the beginning of the first nocturne at Matins, one of the three main sections of the Matins service.

Results so far

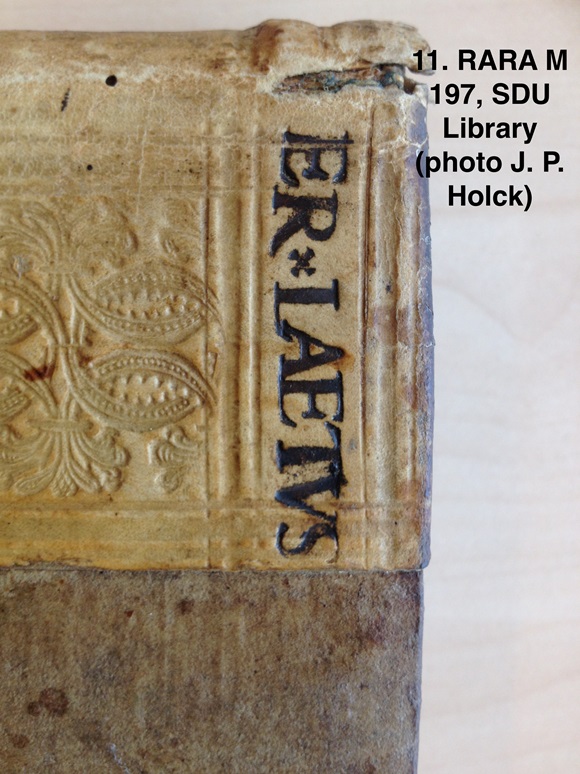

My work with the fragments from the Herlufsholm collection has been a four-month collaboration between the library and the Centre for Medieval Literature, and due to its short timeframe most of the work that I have done has been directed to the most basic questions: What type of manuscripts do the fragments come from, what texts do they contain, what kind of information can be gleaned from them, and to what extent can we say anything about dating and manuscript provenance? Since my scope has been mostly limited to liturgical fragments, these questions have in some cases been fairly easy to set down, based on the available information as outlined in the previous section. For the most part the fragments come from breviaries and missals, or possibly some of the other books that contain chants for the office (antiphonaries) or the mass (sequentiaries, graduals). The fragments have not yet been conclusively dated, because my own experience is not great enough to make any conclusive statements in this regard. As for the provenance, this question can for the most part only be answered tentatively with recourse to the fragment carriers. In the case of Herlufsholm, these books are, as mentioned above, printed in England, Germany or Switzerland for the most part, meaning that the fragments most likely come from these countries as well. For example, RARA Musik M 4 is likely from Northern Germany, as the fragment carrier – Michael Praetorius’ Polyhymnia Caduceatrix et Panegyrica – was printed in Wolfenbüttel in 1619. Moreover, RARA M 197 is likely from Switzerland, as its fragment carrier, Plotini Diuini illius e Platonica familia Philosophi De rebus Philosophicis libri LIIII in Enneades sex distribute by Marsilio Ficino, was printed in Basel in 1559.

In other words, most of the books and most of the fragments have their provenance outside of Denmark, but they are nonetheless important parts of the intellectual history and the book history Denmark since they allow us to shed more light on the books that were available to Danish intellectuals in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. In the case of RARA M 197, moreover, we can also catch glimpses of the libraries of important intellectual figures, as this book was owned by the Danish humanist Erasmus Laetus (1526-82) who carved his name in the cover of the book’s spine.

One of very few fragments that have so far been identified as most probably being of Danish provenance – or at least taken from a Danish religious institution – and that is RARA L 31. This fragment, belonging to a breviary and containing chants for the office of Sundays in the summer, is used as binding for a first edition of Tyco Brahe’s Epistolarum Astronomicarum Liber Primus, printed at Uranienborg in 1596. This book, along with Brahe’s Historia Coelestis and De Nova Stella, has recently been digitised (link:https://www.sdu.dk/da/bibliotek/materialer/om+samlingerne/herlufsholm/brahe/epistolarum+astronomicarum) by the university library under the auspices of Majken B. E. Christensen, Jakob Povl Holck, and Bertil F. Dorch.

The remaining fragments of Herlufsholm will most likely also be digitised in the near future, and that is just one of the steps in the curating of these fragments, along with cataloguing and identifying them. The data that we gather from these fragments, and also from the books in which they are used, provide us with an opportunity to shed more light on the individual fragments, on the book production of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and also on the intellectual history of Denmark. Much of the groundwork has been done in these months, but there are still more discoveries to be made, and more information to be gleaned.