Introduction

In democratic South Africa, freedom lives alongside oppression, where particularly young black women continue to survive perilous lived realities in a society that has consistently been declared one of the most unequal by the World Bank since 2018 (World Bank, 2018: xv). Structural inequality in the country has persistently increased since the end of apartheid despite the establishment of its constitutional democracy in 1994, founded on the redistributive principles of dignity, equality and social justice. These principles were to be achieved, inter alia, through the collective realisation of civil, political and socio-economic rights. At the same time, the democratic dispensation has been lauded for developing one of the most comprehensive social protection systems on the continent. The World Bank describes South Africa’s approach to social protection as an effective mechanism in addressing both poverty and inequality, underpinned by ‘a combination of commitment, leadership, backing from the Constitution, focus on technical soundness, broad countrywide dialogue, and engagement with civil society contributed to this success’ (Bruni, 2016a:120). This anomaly raises a question on the opportunities and limitations of South Africa’s approach to realising socio-economic rights, and particularly social protection, as one means to address structural exclusion in the country.

I argue that South Africa’s current approach to expanding social protection centred on the delivery of cash-based social grants as a means to address income inequality alone, is insufficient. Achieving substantive equality requires the collective realisation of additional socio-economic rights – such as access to adequate health care, food, water and sanitation. While the distribution of a permanent and universal basic income grant (UBIG) is a necessary poverty-alleviating intervention, greater interrogation of the current approach to social protection expansion is required.

Background to structural exclusion in South Africa

Official statistics released by Statistics South Africa have consistently exposed the racialised and gendered nature of the country’s socio-economic landscape. The racialised dimension of inequality in the country has seen white South Africans improving their economic status in post-1994 South Africa, while a disproportionate number of black South Africans, and predominantly black women, remain poor (Farouk and Leibrandt, 2018). Mindful of its intersection with poverty and inequality, by 2021, the official unemployment rate for women was 37,3 per cent compared to 32,9 per cent for men. For black African women, however, the official unemployment rate was higher at 41,5 percent, compared to 9,9 per cent amongst white women, 25,2 per cent amongst Indian women and 29,1 per cent amongst so-called ‘coloured’ women (StatsSA, 2021a). Poverty and unemployment in South Africa further disproportionately affect its younger demographic. Young people aged 15-34 account for 59,5 per cent per cent of the total number of the country’s officially unemployed persons, the majority of whom are young black African women (StatsSA, 2021b). At least one in five South African women have experienced some form of gender-based violence, the frequency of which bears direct correlation with one’s socio-economic status (StatsSA, 2020). These structural fault lines were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Indeed, South Africa’s unequal reality is not unique. Globally, liberal democracies are confronting contradictions that underpin their foundation, particularly as it pertains to the advancement of human rights and social justice everyone. Over the past two decades inequality has increased within countries where the gap between the average incomes of the top 10 per cent of individuals and the bottom 50 per cent has nearly doubled (World Inequality Lab, 2022). As a consequence of this global increase of wealth and income inequality in democracy, the emancipatory potential of human rights to address socio-economic disparities is under threat.

In South Africa, many gains have been made in realizing some of its constitutional ideals through expanding access to education, housing and health care, and poverty reduction generally. However, the deepening levels of poverty alongside the rates of unemployment that reinforces structural inequality, has resulted in the vast majority of its citizens dependent on the state to survive. Close to one third of the South African population – roughly 17,8 million people - were recipients of state-funded social assistance grants prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. South Africa has introduced several targeted programmes for social assistance through its Department for Social Development (DSD), including a child support grant for children under the age of 18; a care dependency grant; foster child grant; disability grant; older person’s grant; war veteran’s grant; and grant-in-aid. All of these grants are means-tested and funded through general state revenue.

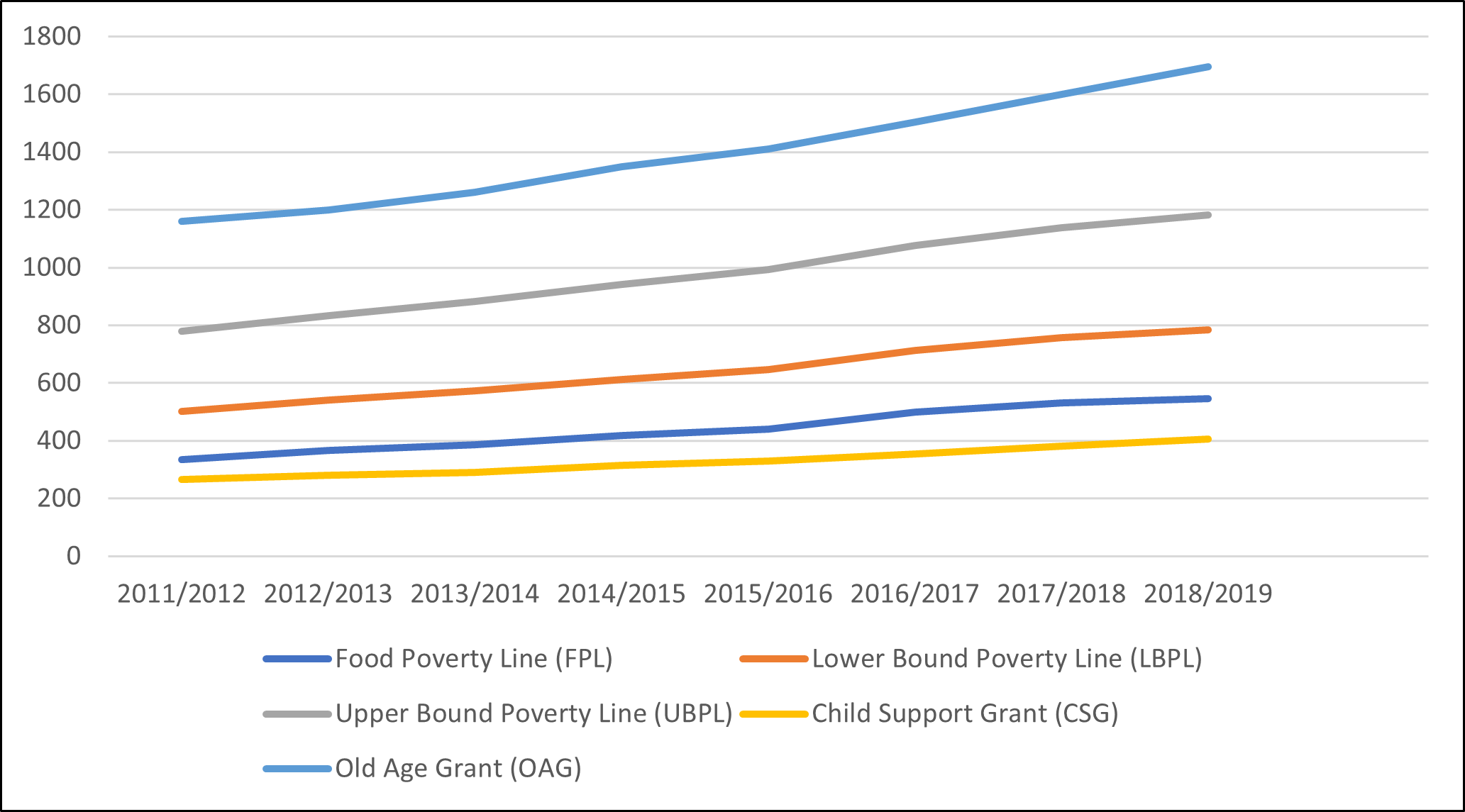

Despite this perceived success, the state has yet to introduce a UBIG, leaving many young formally unemployed black women destitute. For those who are recipients of social protection, it is by virtue of their caregiving status for children, people with disabilities or the elderly. Irrespective of the incremental expansion of social protection to cover more beneficiaries over the past 28 years of the country’s democracy, social protection expenditure has remained largely the same over the past decade at roughly 3 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 16 per cent of the government’s consolidated expenditure. Despite the large proportion of grant income targeted at children and their caregivers, the child support grant has consistently fallen below the national food poverty line. Consequently, the World Bank’s claims that South Africa’s approach to social protection is indeed an effective poverty-alleviating mechanism is questionable (Matthews, 2020).

Figure: National poverty lines and social grants (Rands per person),

2011/2012 - 2018/2019

Source: StatsSA – National Poverty Lines (own calculations)

What could be done differently?

Recent research published by the Black Sash argues that the emphasis of cash-based social grants to alleviate poverty centres the needs of an individual primarily to participate in the market economy Metz, 2016; Plagerson et al, 2019). While cash-based grants are essential, money alone does little to eliminate the sources of vulnerability that perpetually marginalize black women who are poor in South Africa, such as confronting domestic and gender-based violence or addressing their psycho-social needs. It is through the delivery of additional rights – such as sufficient food, healthcare, housing, education, water and sanitation – that the well-being of both the individual and society is achieved (National Planning Commission, 2012; Hochfeld, 2015; Patel 2017).

The Bill of Rights aims to advance redistributive justice through the collective realization of socio-economic rights as citizenship rights. However, the individualized approach that underpins the social grant policy framework has also fragmented relational networks by separating beneficiaries as individuals distinct from their network of caregivers. If premised on values of ubuntu, i.e. the notion of African humanness as a core interpretation of dignity espoused in the country’s constitution, the effectiveness of social assistance policies to tackle poverty is to recognize the interconnectedness between grant beneficiaries within households and their broader communities, rather than as isolated individuals (Whitworth and Wilkinson, 2013). Yet, instead of supporting historically marginalized communities as a redistributive mechanism that allows grant beneficiaries to advance a dignified life, individualized grants have become a survival mechanism for communities who are compelled to pool together limited resources.

Interventions such as a UBIG remain urgently necessary to address the socio-economic threats that arise from the combined poverty, unemployment and inequality in South Africa. However, when considering social protection expansion, it is crucial to interrogate how post-apartheid laws and policies regulating the administration of social assistance has been limited in addressing the multifaceted nature of discrimination experienced by poor black women as a consequence of the intersection of their race, gender, class and age. The current approach of the provision of social grants alone as the primary component of social protection and with a view to combat income inequality is insufficient for the advancement of substantive equality and dignity in the broader political, economic and social landscape of democratic South Africa.

25 October 2022

PhD Candidate: ISS, Erasmus University Rotterdam; School of Law, University of the Witwatersrand

References

Farouk, F. & Leibbrandt, M. (2018) “Inequality in South Africa: Beyond the 1%”, Daily Maverick, 19 July 2018, available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-07-19-inequality-in-south-africa-beyond-the-1/

Hochfeld, T. (2015) ‘Cash, Care and Social Justice: A Study of the Child Support Grant’, Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand.

ILO (2021) ‘Ambitious social protection strategy aims to achieve 40% coverage in Africa by 2025’, Abidjan: International Labour Organization, November 2021.

Matthews, T. (2020) ‘Traversing the cracks: social protection toward the achievement of social justice, equality and dignity in South Africa’, Southern Centre for Inequality Studies Working Paper No. 5, 1-36.

Metz, T. (2016) ‘Recent philosophical approaches to social protection: From capability to ubuntu’, Global Social Policy, 16)2), 132-150.

National Planning Commission (2012) National Development Plan, 2030 (NDP), Pretoria: Government of the Republic of South Africa.

NEDLAC (2019) NEDLAC: Futures of Work in South Africa, March 2019.

Patel, L. (2017) ‘The Child Support Grant in South Africa: gender, care and social investment’ in J. Midgely, E. Dahl & A. Wright (eds) Social Investment and Social Welfare – International and Critical Perspectives, Northampton: Edward Elgar, 105-122.

Plagerson, S., Hochfeld, T., & Stuart, L. (2019) ‘Social Security and Gender Justice in South Africa: Policy Gaps and Opportunities’, Journal of Social Policy, 48(2), 293-310.

StatsSA (2020) Crimes against women in South Africa, an analysis of the phenomenon of GBV and femicide, July 2020.

StatsSA (2021a) ‘Quarterly Labour Force Survey, Q3:2021’, available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14957

StatsSA (2021b) ‘Quarterly Labour Force Survey, Q1:2021’, available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02111stQuarter2021.pdf

Whitworth, A. & Wilkinson, K. (2013) ‘Tackling child poverty in South Africa: Implications of ubuntu for the system of social grants’, Development Southern Africa, 30(1), 121-134.

World Bank (2018) Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: An assessment of drivers, constraints and opportunities, Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Economic Forum (WEF) (2017) “The Future of Jobs and Skills in Africa – Preparing the Region for the Fourth Industrial Revolution”, May 2017.

World Inequality Lab (2022) World Inequality Report: 2022.