Grandparents form an integral part of well-functioning families and by extension communities. Not only is their presence vital to the developmental abilities of grandchildren (Duflo, 2000), but in many instances they also play a significant supportive role to parents in relation to the physical, emotional, and financial care of their children (Barranti, 1985; Burton, 1992). However, when grandparents are left to be full-time caregivers at a point in their lifecycle where they may themselves be in need of care, this highlights significant care gaps left by the state and market and has important consequences for the well-being of such grandparents and the development of the children in their care.

The role of grandparents has become particularly critical in recent decades as women entered the labour market in greater numbers, but also as households became increasingly dependent on dual incomes; leaving parents with a reduced ability to develop and support their children (Jendrek, 1993; Cantillon, Moore and Teasdale, 2021). Without universal access to care services, their unpaid work as carers thus subsidises the state and the market. As research has shown, when there is such a great reliance on households for services (particularly childcare services), inequalities between poorer and wealthier households as well as men and women within the same household are likely to be entrenched (Lloyd and Gage-Brandon, 1993; Hess, Ahmed and Hayes, 2020).

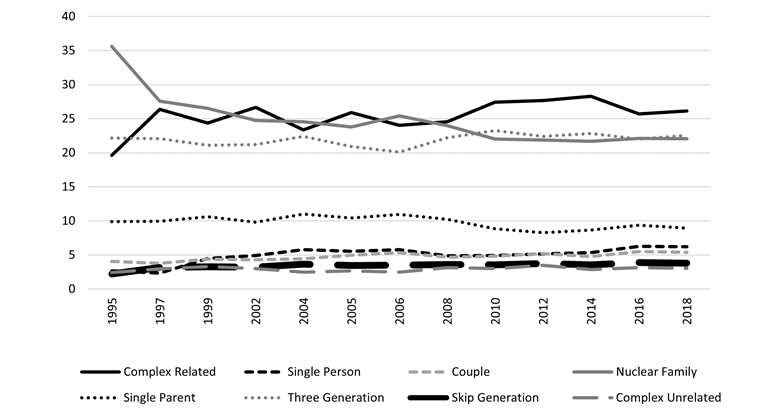

This is no different in the South African context where a decline in nuclear family households (i.e., a household with parents and children) and an increase in complex households, such as three-generation, multigeneration and other complex formations of related individuals have become evident(see Figure 1) (see also Budlender, 2010). Many of these households, particularly multigeneration households, include grandparents who perform varying degrees of care responsibilities in relation to both the adults and the children in the home, but in one of these household configurations it is possible to isolate the extent of these care responsibilities: the skip-generation household.

Figure 1: Share by Household Type, 1995-2018

Source[1]: OHS (various years) & GHS (various years). Note: Extended-type households as a category (not shown here) includes complex related, three generation, skip-generation, and multi-generation households. Complex related households include any formation in which all individuals in the household are related, but that do not fit the definition of the three latter categories.

Skip-generation households are households in which grandparents undertake full-time responsibility for the children in their household in the absence of their parents.[2] From 1995, the proportion of skip-generation households have almost doubled from 2.23% of all households to 3.8% in 2018 (3.9% in 2016). While this is a small share of the population, the absence of a parent (which distinguishes this type of household) places a severe burden on primary caregivers in such households who tend to be elderly individuals with limited or no labour market engagement. This leaves such households in a fragile state and have been likened to child-headed households (Hall and Mokomane, 2018). Further worth noting is that the increase in proportion was not only limited to skip-generation households, but also complex-related households, and a slight increase in the proportion of three-generation households. The growing proportions of more complex household compositions also show an increase in households in which multifaceted care arrangements are likely to take place. However, none allow for an isolation of care in the way that skip-generation households do.

Skip-generation households are vulnerable in two respects, firstly in relation to the characteristics of the individuals who head these households. Using data from the 2018 General Household Survey and comparing characteristics of skip-generation households to the average of all types of households in the sample, skip-generation household heads have a number of characteristics which would leave them and other household members socially and economically vulnerable.

More than two-thirds of skip-generation household heads are female (64%), while almost half are widowed (46%) (Table 1). This indicates that a large number of skip-generation household heads act as single caregivers, where children in need of care are present in the household. More than half of the household heads of skip-generation households were 65 years and older (compared to only 13% of all household heads), while 71% of them were not economically active (NEA) and would thus not be drawing a salary from the labour market.

Table 1: Characteristics of household heads, 2018

|

Female-headed |

Widowed |

65 years and older |

NEA |

|

|

Skip-generation |

64.428 |

46.124 |

55.517 |

71.315 |

|

All |

42.531 |

13.155 |

13.049 |

25.367 |

Source: GHS 2018.

Second, skip-generation households are more vulnerable given their composition in terms of the number of children living in these households, and the average number of adults to children. The average number of children per household in South Africa, when taking the entire sample into consideration, was 2.1 children while the average for skip-generation households was 2.3 in 2018.

Table 2: Average number of children under 18 years of age, 2018

|

Average |

|

|

Skip-generation |

2.306 |

|

All |

2.128 |

Source: GHS 2018.

The combination of the composition of skip-generation households and the characteristics of their heads not only point to households in which the heads and their dependents are vulnerable, but also households in which greater support is needed in relation to the care of the children (and possibly the adults in the households). While the characteristics of a skip-generation household would allow members of such households to be covered by social assistance programmes in South Africa (through the old-age pension and child-support grant, for instance), these programmes are aimed at ensuring individual welfare, rather than taking into consideration the formation and composition of the households in which recipients live. In addition, the small value of the child support grant, in particular, does not provide sufficient funding for all the financial needs related to the care of a child. For many such households, this renders the social assistance programmes somewhat ineffective (Klasen and Woolard, 2009; Mackett, 2020). Although cash transfer programmes tend to be focused on the individual for a variety of good reasons, it is important to consider related characteristics of such individuals to ensure that other factors do not undermine the benefits which such programmes are aimed at delivering. Though they form a small proportion of households, skip-generation households stand out as a particularly vulnerable household type in the South African context and beyond, and it may be beneficial to place a spotlight on such households in future research agendas.

17 August 2023

Odile Mackett is a senior lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand's School of Governance.

[1] This includes data from the South African October Household Survey (1995, 1997, and 1999) and the General Household Survey (2004, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018). All data used in this article were weighed.

[2] In the October Household Survey and General Household Survey questionnaire, relational roles are assigned to individuals in the household, based on their relationship to the household head. In the samples analysed, there were no parents (of the household head) or children (of the household head) present in the household, but grandchildren (of the household head) are in fact present. This is what constituted a skip-generation household and distinguished it from a multigeneration or three generation household. However, it is worth noting that someone listed as a grandchild need not necessary be a minor (i.e., under the age of 18 years of age), but could also include adults who live with their grandparents. About a quarter of the individuals in skip-generation households listed as grandchildren were adults.

References

Barranti, C.C.R. (1985) ‘The Grandparent/Grandchild Relationship: Family Resource in an Era of Voluntary Bonds.’, Family Relations, 34(3), p. 343. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/583572.

Budlender, D. (2010) ‘South Africa: When marriage and the nuclear family are not the norm’, in Time use studies and unpaid care work. Routledge.

Burton, L.M. (1992) ‘Black grandparents rearing children of drug-addicted parents: stressors, outcomes, and social service needs’, Gerontologist, 32(6), pp. 744–751.

Cantillon, S., Moore, E. and Teasdale, N. (2021) ‘COVID-19 and the Pivotal role of Grandparents: Childcare and income Support in the UK and South Africa’, Feminist Economics, 27(1–2), pp. 188–202. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2020.1860246.

Duflo, E. (2000) Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old age pension and intra-household allocation in South Africa. 8061. Cambridge. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w8061.

Hall, K. and Mokomane, Z. (2018) ‘The shape of children’s families and households: A demographic overview’, South African Child Gauge, p. 45.

Hess, C., Ahmed, T. and Hayes, J. (2020) Providing Unpaid Household and Care Work in the United States: Uncovering Inequality. Briefing Paper 487. Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Jendrek, M.P. (1993) ‘Grandparents who parent their grandchildren: effects on Lifestyle’, Journal of Marriage and Family, 55(3), pp. 609–621. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/353342.

Klasen, S. and Woolard, I. (2009) ‘Surviving unemployment without state support: Unemployment and household formation in South Africa’, Journal of African Economies, 18(1), pp. 1–51. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejn007.

Lloyd, C.B. and Gage-Brandon, A.J. (1993) ‘Women’s role in maintaining households: Family welfare and sexual inequality in Ghana’, Population Studies, 47(1), pp. 115–131. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000146766.

Mackett, O. (2020) ‘Social Grants as a Tool for Poverty Reduction in South Africa? A Longitudinal Analysis Using the NIDS Survey’, African Studies Quarterly, 19(1), pp. 41–64.