Student satellites can contribute with important knowledge in the fight against climate change

A group of students from The University of Southern Denmark are together with students from several other Danish universities developing two satellites that can contribute to our understanding of the climate changes. Soon, they will send the first satellite into space.

For Nikolaj Forskov Eriksen, it began as a joke. He was sitting in a break on the first semester of his electrical engineering program and said in jest to some classmates that it would be cool to make a satellite and send it into space.

Now, two years later, it is no longer a joke.

In the beginning of February 2023, the bachelor's student from the University of Southern Denmark will together with a fellow student from Aarhus University travel to Vandenberg Space Force Base in California with the student satellite DISCO-1 in their hand luggage with the purpose of mounting it in one of Elon Musk and SpaceX's rockets.

Meet the Student

The 41-year-old future electrical engineer has a background as a conservatory-trained violinist and folk musician, but a few years ago he decided to change tracks and rediscover his old interest in copper wires and solder.

- I've always tinkered with electronics and got a radio broadcast license when I was 15. I've probably always been fascinated by space too. As a kid, I used to look at planets with a telescope with a friend, says Nikolaj Forskov Eriksen.

- But I never imagined I would be doing something like this when I started at the University of Southern Denmark.

Meet the researcher

Nicolai Iversen is Dream Office Manager at the Faculty of Technology. He works to strengthen recruitment for student projects.

- It's crazy. I sat just over there soldering a board that will go into a satellite and placed into orbit, says Nikolaj Forskov Eriksen, as he gives a guided tour around the project's facilities on the University of Southern Denmark's campus in Odense.

Satellites against climate change

DISCO-1 is the first of two satellites, which are developed and

operated by students at the University of Southern Denmark, Aarhus

University, Aalborg University and the IT University of Copenhagen.

They will all be sent into space, and the students are also

building a ground station and placing a giant parabolic antenna on

the roof of the Technical Faculty in Odense, so they can

communicate with the satellites.

”If we want to have any idea of the natural emissions we can expect, and how we should respond to them, we need information on how and where the ice is melting in the Arctic

- If we want to have any idea of the natural emissions we can expect, and how we should respond to them, we need information on how and where the ice is melting in the Arctic, and how the Arctic affects emissions and the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Otherwise, we don't know how much we should mitigate in the future to reach net zero.

There are already satellites that monitor the area, but none of them are dedicated to this task specifically. Therefore, the climate professor sees the students' satellite as a welcome supplement, also for field expeditions.

- The Arctic is an inaccessible region. It is difficult, logistically, and often you can't get out due to climatic conditions. Therefore, the satellites are a good and useful tool, because they can look down from above and contribute both with detailed regional knowledge and help to create an overview. As long as there is no cloud cover, that is.

10km per second

However, the first satellite to be sent up in 2023, is entirely for

proof of concept, says Nikolaj Forskov Eriksen and opens the door to

the temporary control room filled with screens and flashing computers.

It will be DISCO-2, which is planned to be launched in 2024, that will be equipped with up to three cameras and send pictures back that can be used to create detailed 3D visualizations of the glaciers and their decreasing mass.

The mission of DISCO-1 is to prove that the students can get in touch with the satellite and get it to turn the right way in the short periods of time it passes the Arctic.

-The satellite can go around the earth in 90 minutes and has an average speed of 10 kilometers per second, so we only have about 15 minutes to get in touch with it when it passes over us, he says.

Not that easy

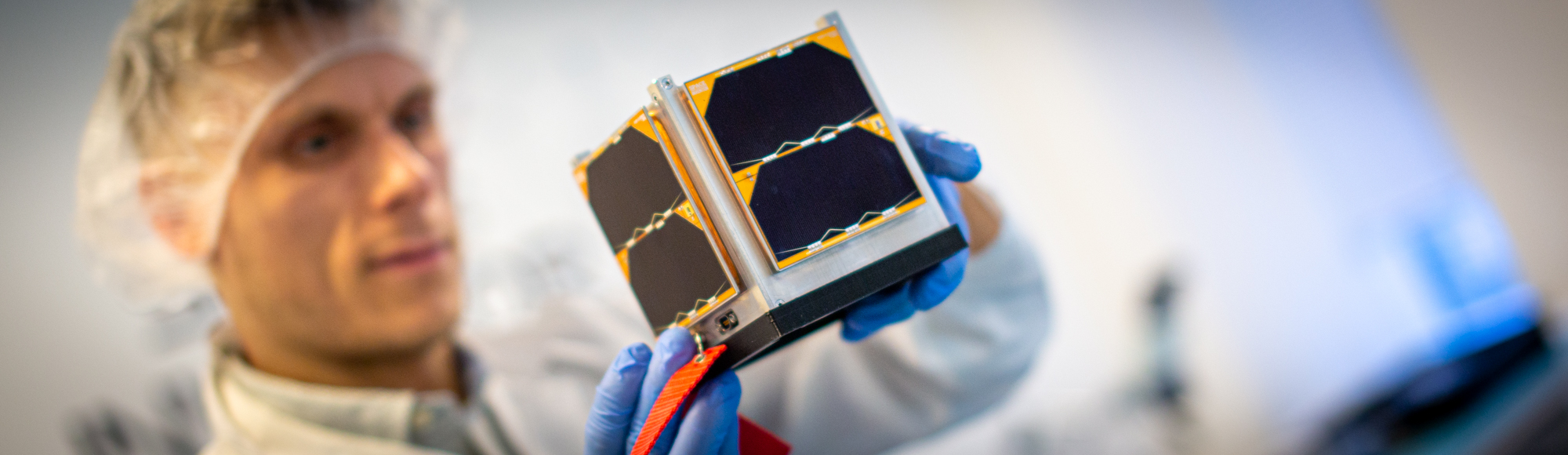

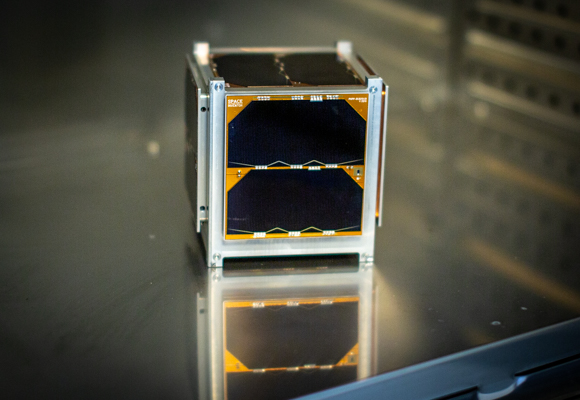

Nikolaj Forskov Eriksen brings out a model of the satellite. 10 x 10 x

10 centimeters are the measurements, which in the space research world

is known as 1 unit.

The satellite is a so-called CubeSat. It is built according to the square standard measurements that are used all over the world, so you do not have to specially design rockets and deployers every time you make a new satellite. You can also put several of the squares together, and then you get a satellite of, for example, 2, 3 or 6 units.

The DISCO satellites will be darting through the thermosphere at an altitude of around 400 kilometers, and in order to pass the Arctic, they need to be in a polar orbit. This means that they rotate around the earth from pole to pole, not along the equator.

And that's not quite straightforward, Nikolaj Forskov Eriksen explains:

- The Falcon-9 rocket that our satellite will be launched upon doesn't pass by the poles, so our satellite will have to be on board a smaller vessel on the rocket. This vessel will be dropped off at an altitude of 400 kilometers close to the equator and then fly up to the North Pole, where our satellite can finally be launched.

Many different challenges

In general, it is extremely complex to develop a satellite that

actually works in space, says Associate Professor of Particle Physics

at University of Southern Denmark, Mads Toudal Frandsen. He is one of

the main forces behind the SDU Galaxy research network, which the DISCO

satellites belong to.

- There are many different challenges. First, you have to develop the entire satellite payload, that is, everything that needs to be implemented in the satellite to make it do something, such as sensors and cameras. And then you have to get all the components to work together. You also need to be able to communicate with the satellite from the ground, explains Mads Toudal Frandsen.

- And then you have to get all of this to work in space, where you can't just grab the satellite and change something, and where there is also limited power from the small solar panels available.

Overheating in the cold

The launch itself, of course, also exposes the satellite to some

violent shakes, a huge acceleration and therefore G-forces. And in

space, there is a special environment that the satellite must be able

to withstand, says the particle physicist.

- In outer space, it is extremely cold. 2.7 kelvins to be precise, or 2.7 degrees above absolute zero which is -273.15 degrees Celsius. Maybe it's a bit warmer closer to Earth, where the satellite is, but it's still very, very cold, says Mads Toudal Frandsen.

But actually, it it's not the cold that's the problem. Paradoxically, it's the risk of overheating of the components.

Space research in Odense

The network was formed in 2021 by Lecturer in Physics, Mads Toudal Frandsen and Specialist Consultant Nicolai Iversen, because there was a need for a place at SDU where both researchers and students with an interest in space could come together for projects.

- At University of Southern Denmark we have no tradition of developing or teaching space technology, but we have some of the best researchers and teachers in fields like robots, drones, AI, electrical and mechanical systems, which are all important parts of developing satellites, says Nicolai Iversen

- That is the reason we started SDU Galaxy. And we can see that our students thrive with the many possibilities and grow with the demanding responsibility. It is after all the first time Danish students are travelling to SpaceX to integrate their own satellite.

In addition to the DISCO project, students in SDU Galaxy are also working on building a ground station to communicate with satellites and a rover that can drive around on planets in space.

It is also SDU Galaxy that has been the main driving force behind getting the national space conference to SDU in 2023.