New insight: Why only some develop liver disease from the same genetic condition

An international team of researchers, including participants from the University of Southern Denmark (SDU), has used advanced technology to uncover why only some patients with a hereditary liver disease go on to develop serious illness. The results have now been published in Nature.

Although around 2,500 people in Denmark carry the same genetic mutation, only a small number go on to develop severe liver disease. Why this happens – or doesn’t happen – has long remained a mystery.

Now, researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, SDU, Odense University Hospital, and the University Hospital in Aachen have found new answers.

They investigated the inherited disorder alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, where a defective protein builds up in the liver.

A closer understanding of the cause

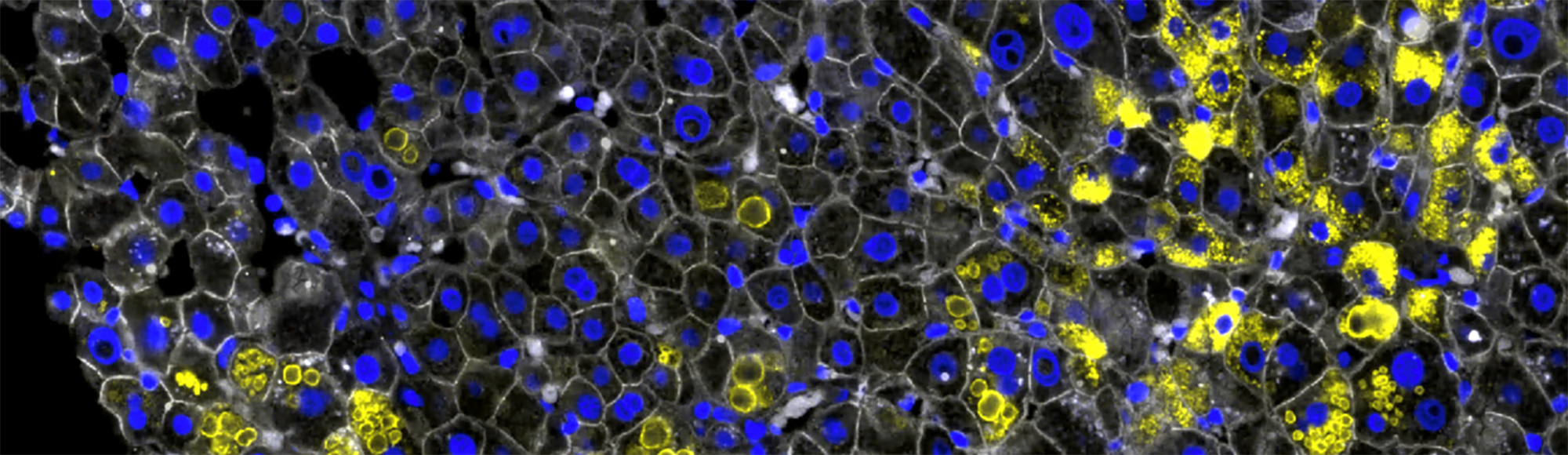

By isolating individual cells from liver tissue using laser microdissection and analysing their protein content, the team was able to determine which damage and defence mechanisms liver cells activate in response to the protein build-up.

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- Caused by a mutation in the SERPINA1 gene. The mutation leads to misfolding of the protein alpha-1 antitrypsin, which accumulates in liver cells and is lacking in the bloodstream – hence the name.

- Around 2,500 people in Denmark have the severe disease variant known as ZZ.

- 20–35% of those with the ZZ variant develop significant liver scarring (fibrosis).

- Around 13% of ZZ carriers experience serious or life-threatening liver complications.

- Currently, there is no approved medical treatment for liver damage caused by the disease.

- The study used a method called Deep Visual Proteomics, where researchers isolate single cells from tissue and analyse their protein content.

This gave them a highly detailed insight into how, in some cases, the body is able to halt the disease before it progresses. It brings the research team closer to understanding why only some individuals with the genetic mutation go on to develop liver disease.

– For the first time, we’ve been able to see what protects some patients from severe liver damage – even though they have exactly the same genetic disease as others, says Professor Aleksander Krag, professor and research director at FLASH – Centre for Liver Research and co-author of the study.

– We’ve been able to analyse what’s happening at the level of the individual liver cell – this has provided us with a truly unique insight into the disease, adds Katrine Thorhauge, medical doctor, PhD student and co-author.

A disease with many trajectories

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is a hereditary condition caused by a mutation in the SERPINA1 gene. It results in a malformed protein accumulating in liver cells and being deficient in the blood. In some individuals, this leads to damage in the liver and lungs – in others, it does not.

Using new technology, the researchers were able to analyse changes in individual liver cells. They discovered, for instance, that some cells activate an early protective response that can prevent the development of liver disease.

– By reviewing patient histories, we saw that those with severe fibrosis lacked the early peroxisomal response, says Florian Rosenberger, first author and researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry. – We now know this response is protective. Our goal is to develop an early warning system for liver fibrosis – a way to identify patients at risk before symptoms arise.

SDU researchers contributed essential knowledge

In addition to their clinical insight, the research team in Odense contributed tissue samples from patients with mild liver disease, making it possible to compare early and late stages of the disease.

The liver biopsies were analysed by Sönke Detlefsen, professor at the Department of Clinical Research and consultant at the Department of Clinical Pathology (Odense University Hospital), who also contributed as a co-author. Using microscopy, histochemistry and immunohistochemistry, he assessed the stage of fibrosis and the extent of alpha-1-antitrypsin accumulation. A selection of biopsies was sectioned, mounted on membranes and forwarded to the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry.

– It has been crucial to have access to tissue from patients who, despite carrying the genetic mutation, have not become seriously ill. This has given us new knowledge about how the liver attempts to protect itself, says Aleksander Krag.

The results have just been published in the prestigious journal Nature, and the researchers hope their findings will lead to earlier identification of patients who are likely to develop severe liver disease – and perhaps even contribute to the development of new medical treatments.

Meet the researcher

Katrine Thorhauge is a medical doctor and PhD student at the Department of Clinical Research and FLASH – Centre for Liver Research at Odense University Hospital.

Meet the researcher

Aleksander Krag is professor and head of research at Department of Clinical Research and FLASH - Centre for Liver Research, Odense University Hospital.

Meet the researcher

Sönke Detlefsen is a professor at the Department of Clinical Research and consultant at the Department of Clinical Pathology (Odense University Hospital).