Completely New Ecosystem Discovered at 9,500 Meters Depth

When a research team reached the bottom of a deep-sea trench, they suddenly found themselves surrounded by thousands of unusual animals thriving in the cold, dark deep.

“This shows how much more can be discovered when diving with a submersible and directly observing the seabed, rather than only bringing up samples ‘blindly’,” says deep-sea researcher Ronnie N. Glud, co-author of a new article published in Nature (find it here).

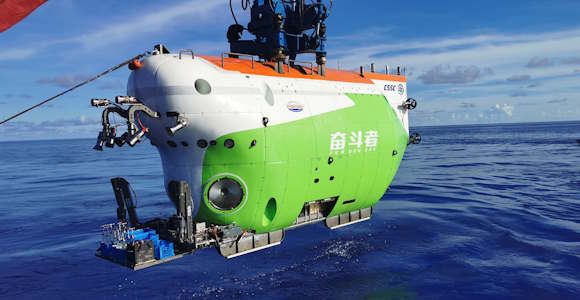

The discovery was made during a recent expedition to two deep-sea trenches in the northern Pacific, where researchers had the opportunity to dive in one of the world’s most advanced submersibles, the Chinese Fendouzhe. Over the course of the expedition, Fendouzhe completed 23 dives. On 19 of these, the three crew members repeatedly observed vast areas teeming with life: tube worms, mussels, and other creatures.

What the team found were the deepest chemosynthetic vent ecosystems ever recorded on Earth.

The most striking features were dense colonies of white mussels and tube worms with bright red, hemoglobin-rich tentacles. These ecosystems were observed along a 2,500 km stretch at depths ranging from 5,800 to 9,533 meters.

The colonies were located in the Kuril-Kamchatka Trench and the western Aleutian Trench, off Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula.

“We previously had hints that such ecosystems might exist in this region, but we had no idea they extended into the deep central parts of the trench. It is truly remarkable to find such a rich biodiversity of large animals along the trench axis. Samples from other trenches have provided valuable information about conditions in the deep trenches, but until now they have not offered strong evidence of extensive ecosystems of this kind,” says Glud, an expert on deep-sea trenches and head of the Danish Center for Hadal Research at SDU.

The expedition was led by Chinese researchers from the Institute for Deep Sea Science and Engineering (IDSSE) in collaboration with Russian scientists, and it took place in Russian territorial waters. For this reason, Western researchers were unable to participate directly in the expedition following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

For the same reason, a large-scale German-led expedition with participation from Glud and the HADAL team had to be redirected to the eastern Aleutian Trench, located in U.S. waters off Alaska. There, no extensive chemosynthetic ecosystems were found, but many other discoveries are currently under analysis — but that is another story.

Glud, who has long collaborated with IDSSE researchers, closely followed the expedition, received samples, and helped interpret, compile and write about the results — which is why he is listed as co-author of the Nature article.

“The discovery came as a huge surprise. Nobody expected to find these ecosystems at such extreme depths. They were not the primary target of the expedition — but they soon became the focus,” he explains.

After the initial surprise, an obvious question arose: how can these animals survive at the bottom of a deep-sea trench, where it is freezing cold, pitch dark, and the pressure is immense?

The extensive colonies, some with up to 5,000 individuals per square meter, were found at so-called cold seeps — areas where methane and hydrogen sulfide leak out from the seabed.

“Apparently, there are massive methane deposits beneath these newly discovered cold seeps. They provide the nutritional foundation for the growth of microorganisms — and in turn, for the entire ecosystem we see down there,” says Glud.

Here, microorganisms (bacteria and archaea) feed on the seeping methane and hydrogen sulfide. Some live freely in the sediment, while others exist in symbiosis with mussels and tube worms, living inside them much like gut bacteria live inside the human body.

The extraordinary thing about these ecosystems is that they do not rely on sunlight. Nor do they depend on sinking organic matter from the surface for food. Instead, they are fueled by chemical compounds. In scientific terms, they are chemosynthetic rather than photosynthetic. The microorganisms consume methane and hydrogen sulfide, and when they grow in sufficient numbers, they form the food base for the many unusual animals in the ecosystem.

Results from new expedition

“We already knew that deep-sea trenches concentrate large amounts of sinking organic material from the surface or from coastal zones, which supports diverse microbial communities. But we have long wondered whether chemosynthetic processes could also produce organic matter to sustain life in the deep. Until now, we had only seen smaller contributions — nothing on the scale revealed by this study,” says Glud.

Although the newly discovered ecosystems are classified as chemosynthetic, because the microorganisms depend on methane rather than organic matter, further analysis shows that the methane itself is biologically produced — likely originating from large deposits of organic carbon in deeper sediment layers.

One of Glud’s most recent expeditions, also in collaboration with IDSSE and employing the Fendouzhe, explored the Puysegur Trench south of New Zealand. While the results have not yet been fully analyzed or published, he hints that many exciting new findings were made there as well.

Meet the researcher

Ronnie N. Glud is a professor and head of Danish Center for Hadal Research at SDU. He has participated in more than 50 scientific expeditions.