CPop

Life in a violent country can be years shorter and much less predictable – even for those not involved in conflict

How long people live in violent countries is less predictable and life expectancy for young people can be as much as 14 years shorter compared to peaceful countries, according to a new study today from an international team, led by Interdisciplinary Centre on Population Dynamics, University of Southern Denmark and Oxford University.

The study reveals a direct link between the uncertainty of living in a violent setting, even for those not directly involved in the violence, and a ‘double burden’ of shorter and less predictable lives.

According to the research, violent deaths are responsible for a high proportion of the differences in lifetime uncertainty between violent and peaceful countries. But, the study says, ‘The impact of violence on mortality goes beyond cutting lives short. When lives are routinely lost to violence, those left behind face uncertainty as to who will be next.’

Lead author Dr José Manuel Aburto from Interdisciplinary Centre on Population Dynamics, University of Southern Denmark and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine adds:

”What we found most striking is that lifetime uncertainty has a greater association with violence than life expectancy. Lifetime uncertainty therefore should not be overlooked when analysing changes in mortality patterns.

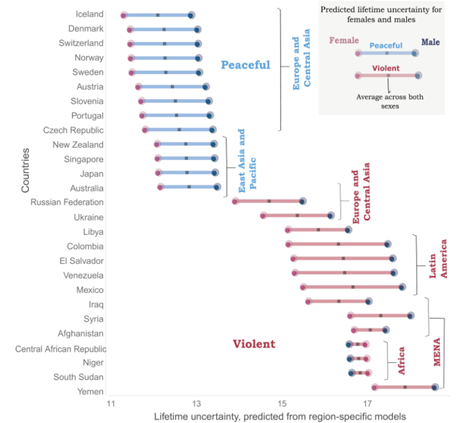

Using mortality data from 162 countries, and the Internal Peace Index between 2008-2017, the study shows the most violent countries are also those with the highest lifetime uncertainty. In the Middle East, conflict-related deaths at young ages are the biggest contributor to this, while in Latin America, a similar pattern results from homicides and interpersonal violence.

But lifetime uncertainty was ‘remarkably low’ between 2008-2017, in most Northern and Southern European countries with Denmark and other Scandinavian countries scoring the best. Although Europe has been the most peaceful region over the period, the Russian invasion of Ukraine will impact this.

In high-income countries, reduced cancer mortality has helped to reduce lifetime uncertainty recently. But in the most violent societies, lifetime uncertainty is even experienced by those not directly involved in violence. The report states, ‘Poverty-insecurity-violence cycles magnify pre-existing structural patterns of disadvantage for women and fundamental imbalances in gender relations at young ages. In some Latin American countries, female homicides have increased over the last decades and exposure to violent environments brings health and social burdens, particularly for children and women.’

Study co-author Professor Ridhi Kashyap from Oxford’s Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science says, ‘Whilst men are the major direct victims of violence, women are more likely to experience non-fatal consequences in violent contexts. These indirect effects of violence should not be ignored as they fuel gender inequalities, and can trigger other forms of vulnerability and causes of death.’

Study figure: Predicted lifetime uncertainty by sex, ranked from highest to lowest lifetime uncertainty across the most violent and peaceful countries.

According to the study, lower life expectancy is usually associated with greater lifetime uncertainty. In addition, living in a violent society creates vulnerability and uncertainty – and that, in turn, can lead to more violent behaviour.

Countries with high levels of violence experience lower levels of life expectancy than more peaceful ones, ‘We estimate a gap of around 14 years in remaining life expectancy at age 10 between the least and most violent countries… In El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala and Colombia the gap in life expectancy with high income countries is predominantly explained by excess mortality due to homicides.’

Study co-author Vanessa di Lego from the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital adds, ‘It is striking how violence alone is a major driver of disparities in lifetime uncertainty. One thing is for certain, global violence is a public health crisis with tremendous implications on population health and should not be taken lightly.’

More information, including a copy of the paper, can be found online at the Science Advances here.

For interviews and briefings, please contact lead author of the study José Manuel Aburto (jmaburto@sdu.dk).

About the Interdisciplinary Centre on Population Dynamics

The Interdisciplinary Centre on Population

Dynamics (CPop) is a cross-faculty collaboration between researchers drawn from

demography, public health, biology, mathematics, economics, political science

and humanities. The center conducts innovative research to discover the basic

causes and key consequences of changes in survival, longevity, and population

aging, including also their economic, policy, and cultural implications. More

information on the Centre can be found here.

Meet the researcher

José Manuel is an Assistant Professor at the Interdisciplinary Centre on Population Dynamics. His research focuses on the development of methodology to understand how populations and individuals survive to higher ages.