Examples of cherry-picking of diagrams can be found in medieval Greek manuscripts

A DIAS research team wishes to get a better understanding of how medieval people thought – and how some of the mechanisms of cherry-picking of diagrams, we know from today, can be detected in texts from a thousand years ago.

There is an old handbook on how to write speeches that still affects how students learn to write a speech and build an argument today.

The handbook was written by the Greek rhetorician Hermogenes, and it is the starting point for a new interdisciplinary DIAS-project that Aglae Pizzone, associate professor at Department of History & Centre for Medieval Literature, SDU got the idea to explore.

- We want to focus our project on the margins of the handbook where dozens of teachers and scholars from year 900 and onwards left commentaries and drew diagrams. We are particularly interested in analyzing the diagrams, because they give us an understanding of how people thought, Aglae Pizzone says.

Aglae Pizzone is a trained classicist from Italy and has studied ancient Greek and Latin with a specialty in Byzantine literature. She has been a DIAS fellow since 2018.

The idea with the project is to analyze the diagrams with methods from the fields of cognitive history, rhetorical thinking, and computer science.

- Hopefully, our work will lead to a better awareness of the use of diagrams in rhetorical sciences, because they can often be misused in for example pseudo-science. If you want to do bad science, what do you do? You put in a diagram. We want to show how this happens in rhetoric - and a careful analysis of these commentaries shows how this already happened more than a thousand years ago, Aglae says.

In the long run, Aglae also want to use the project to prove that the reason the theory in this handbook works so well is because it might function like a computational algorithm.

How did the team find each other?

- The project is called Toward a cognitive history of pre-modern rhetoric as mathematical thinking.

- Aglae Pizzone got the idea and brought the team together.

- Involved in the project besides Aglae Pizzone are Nina Bonderup Dohn, professor and Zhiru Sun, associate professor, both from Institute for Design and Communication, Benjamin Jäger, associate professor, DIAS, IMADA and CP³-Origins and Chiara D’Agostini, former PhD student and project manager at the Center for Medieval Literature, Department of History. Additionally, Anna Bistaffa is hired as research assistant on the project.

- Nina Bonderup Dohn and Benjamin Jäger are also DIAS-fellows.

Collecting the manuscripts

Aglae Pizzone got the idea from the project after surveying the manuscript by Hermogenes, and she reached out to the other researchers.

First, the team wanted to map out the diagrams, so they hired research assistant Anna Bistaffa to analyze a selection of the manuscripts, meaning the different versions of commentary to the handbook, which was phase 1. Most of the data was available through digital libraries and databases.

- Right now, we are in phase 2, which is about analyzing the collected material to understand from a cognitive point of view how these diagrams work, Aglae Pizzone says.

Phase 3 is trying to understand why this original handbook was so popular.

- My answer so far - and what I would like to find evidence of - is that the way Hermogenes presented the building of an argument works like computational thinking, almost like an algorithm, Aglae Pizzone says.

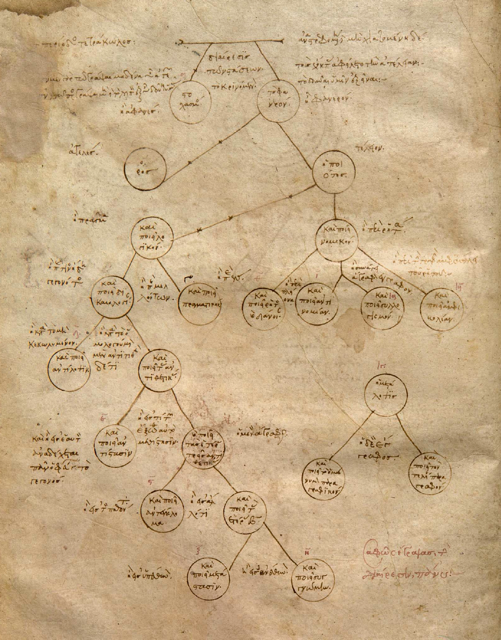

An example of one of the diagrams. Foto by Aglae Pizzone (Naples, II E 5, f. 11r., early 13th s.)

Training an algorithm

- My wildest dream is to train an algorithm based on this theory and map out successful speeches from modern day to see if they worked like the theory said they would, she says.

To be able to train an algorithm, Aglae Pizzone needs input from the other researchers involved. This is where it comes in handy that Benjamin Jäger, who is an associate professor at IMADA, is part of the project.

Aglae Pizzone emphasizes that she would like to be involved in the computational aspects of the project, but that she still has a lot to learn about algorithms.

That is also part of the reason that the cognitive parts come first, where she will be working closely with Nina Bonderup Dohn and Zhiru Sun, both from Institute for Design and Communication, SDU.

- This liaison with cognitive studies is important because it helps us to understand how medieval learners might have thought. It is offering new insights in the understanding of the past, she says.

Fighting pseudo-science

When the project is over, hopefully Aglae Pizzone and her team will have a new understanding of how diagrams were used to make arguments stronger a thousand years ago.

- I argue that the handbook and the medieval commentaries laid the breeding ground for creating the learning system as we know it today: lecturers and scholars engaged with the commentaries, and this paved the way for the modern gymnasium.

But the use of visual aids in the commentaries also shows how cherry picking of diagrams has a long history, that we need to be aware of:

- It is important that we – especially in the current climate – are aware of how diagrams are used. There are publications showing how climate change deniers cherry-pick diagrams and use them to fool the audience. It is important not to discard this, to be alert of what is going on, and not to be led unconsciously in a certain direction, Aglae Pizzone says.