By P. Pedersen

Fig. 1. The city of Halikarnassos. Model by Axel Sønderborg.

Fig. 1. The city of Halikarnassos. Model by Axel Sønderborg.

The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos was built ca 360-350 BC as the monumental tomb of Maussollos, the Hekatomnid satrap and governor of the Persian king. It is situated in the center of the newly re-founded city of Halikarnassos in one corner of a large monumental terrace of about 242m x 105 m (fig. 1). The entrance to the terrace was from a large entrance building on the east wall of the terrace probably leading from the main square, the Agora, of Halikarnassos. Along the north side of the terrace ran the main street of Halikarnassos. It had a width of ca. 15 m and headed directly towards the main west gate of the city, the Tripylon Gate or Myndos Gate. This street still constitutes to-day the main street of Bodrum, the Turgut Reis Caddesi.

Architecture and decoration

Fig. 2. The “Quadrangle” (foundation cutting) for the Maussolleion (K. Jeppesen).

Fig. 2. The “Quadrangle” (foundation cutting) for the Maussolleion (K. Jeppesen).

The Maussolleion was built in a rectangular cutting in the bed-rock measuring about 32.5 x 38.5 m. (fig. 2). The building consisted of three main parts: a tall Podium, which carried a temple-like structure with 11 x 9 Ionic columns, ca 10 m in height and a roof consisting of 24 large steps of marble (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Reconstruction of the Maussolleion. Model by Kristian Jeppesen and Axel Sønderborg.

Fig. 3. Reconstruction of the Maussolleion. Model by Kristian Jeppesen and Axel Sønderborg.

The building was richly adorned with a huge amount of sculptures created by a number of the most famous Greek sculptors of the Late-Classical period: Skopas, Leochares, Bryaxis, Timotheos and possibly Praxiteles. Except for the big quadriga on top of the Maussolleion, the lions along the roof and the Amazon frieze it is still discussed precisely how the remaining groups of sculptures should be distributed on the building.

The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos was included in the list of the Seven Wonders of the World no doubt mainly due to its sculptures.

Afterlife

The Maussolleion stood for many centuries - perhaps well into the 12th century - and is believed by some to have collapsed due to an earthquake about that time. From the time of the Renaissance the building and its owner was of interest to Boccaccio and other Renaissance humanists. Paradoxically imaginative reconstructions of the Maussolleion and Halikarnassos began to appear at about the same time as western crusaders utterly destroyed the remains of the Maussolleion in order to have building materials for the construction of the Castle of St. Peter.

Modern research

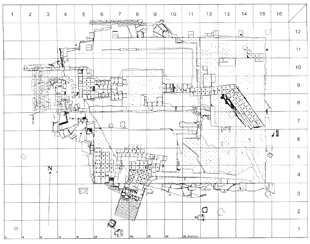

The fundamental modern research on the site of Maussolleion was carried out by a British expedition lead by C.T. Newton in 1857-58 with additional investigation under the direction of A. Biliotti in 1865. The site was re-excavated by Prof. Kristian Jeppesen and a Danish team in 1966-77 and during these works a concise plan of the building site (“the Quadrangle”) was produced for the first time (fig. 4). By this and the painstaking study of thousands of fragments from the excavation site and in the British Museum, Jeppesen managed to produce a far more varied and detailed evidence for the reconstruction of the monument. By combining the physical evidence from the excavations and the descriptions of Halikarnassos and the Maussolleion by Vitruvius (De Arch 2.8.10-15) and Pliny (NH 36.30-31), Jeppesen produced the most well-founded reconstruction of the huge monument till now (fig. 3).

Fig. 4. Plan of the “Quadrangle” (K. Jeppesen).

Fig. 4. Plan of the “Quadrangle” (K. Jeppesen).

There are, however, still uncertainties and problems, which cannot be solved from the existing evidence and new suggestions for a reconstruction of the Maussolleion appear now and then, most recently one by prof. W. Hoepfner in 2013. The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos is unique within Greek architecture and sculpture. The importance of the monument and its cultural context at the end of the Classical period is increasingly acknowledged. In spite of all the work and research already done since the Renaissance, it will continue to fascinate and keep scholars occupied and produce new insights into the formation of the Hellenistic era.

Literature

Literature on the Maussolleion is enormous and only some basic works are mentioned here.

The British Excavations directed by Charles T. Newton

Newton, C.T. 1862: A History of Discoveries at Halicarnassus, Cnidus and Branchidae. London.

The Danish Excavations directed by Kristian Jeppesen

Højlund, F., K. Aaris-Sørensen & K. Jeppesen 1981: The Sacrificial Deposit. The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, vol. 1. Aarhus.

Jeppesen, K. & A. Luttrell 1986: The Written Sources and their archaeological Background. The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, vol. 2. Aarhus.

Pedersen, P. 1991: The Maussolleion Terrace and Accessory Structures. The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, vol. 3.1 and Vol. 3.2. Aarhus.

Jeppesen, K. 2000: The Quadrangle. The Foundations of the Maussolleion and its Sepulchral Compartments. The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, vol. 4. Aarhus.

Jeppesen, K. 2002: The Superstructure. A comparative analysis of the architectural, sculptural, and literary evidence. The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, vol. 5. Aarhus.

Zahle, J. & K. Kjeldsen 2004: Subterranean and pre-Maussollan Structures on the Site of the Maussolleion: The Finds from the tomb chamber of Maussollos (D. Ignatiadou and V. Nørskov). The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, vol. 6. Aarhus.

Vaag, L.E., V. Nørskov & J. Lund 2002: The Pottery: Ceramic Material and Other Finds from Selected Contexts. The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, vol. 7. With a contribution by M.K. Schaldemose. Aarhus.

The Sculpture

Waywell, G.B. 1978: The Free-standing Sculptures of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. London.

Cook, B.F. 2005: Relief Sculpture of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. Oxford.

Recent books and articles

Jenkins, I. 2006: Greek Architecture and its Sculpture in the British Museum. London.

Pedersen, P. 2013: The 4th century BC ‘Ionian Renaissance’ and Karian Identity, in O. Henry (ed), 4th Century Karia. Defining a Karian Identity under the Hekatomnids, Paris, 33-64. (With an appendix on the pre-Maussollan water systems at the Maussolleion site).

Hoepfner, W. 2013: Halikarnassos und das Maussolleion. Darmstadt/Mainz.

Pedersen, P. 2015: On the planning of the Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, in S. Faust, M. Seifert & L. Ziemer (eds), Antike. Architektur. Geschichte. Festschrift für Inge Nielsen zum 65. Geburtstag, Aachen, 153–166

Pedersen, P. 2017: The Totenmahl Tradition in Classical Asia Minor and the Maussolleion at Halikarnassos, in E. Mortensen & B. Poulsen (eds), Cityscapes and Monuments of Western Asia Minor, Oxford, 237–255.

In Danish

Jeppesen, K. 1999: Et klassisk verdensvidunder til revision, in P.G. Bilde, V. Nørskov & P. Pedesen (eds.),"Hvad fandt vi?". En gravedagbog fra Institut for Klassisk Arkæologi, Aarhus, 39-56.

Pedersen, P. 2017: Maussollæet i Halikarnassos, in S.G. Saxkjær & E. Mortensen (eds.), Antikkens 7 Vidundere, Aarhus 2017, 148-187.